Tunnels through the Hills

There are two railway tunnels through the Malvern Hills. The one in present use was built by the Great Western Railway Company and opened in August, 1926. Alongside is the original tunnel, opened in September, 1861 for the Worcester and Hereford Railway Company. Its portals are now crumbling and overgrown and the narrow bore is a melancholy, rubble-strewn, smoke-blackened cave echoing in the long gloom.

The old tunnel measures 1,567 yards between faces, which is no great length. However, the extraordinary toughness of the rock made its construction very difficult indeed. The heart-rock of the Malverns is a very old and very hard granite called syenite which thrusts upwards as a slightly leaning wall, supporting drifts of soil and shale which form the lower slopes. On the Malvern side the slopes are of red marl, and on the Colwall side limestone shales, both much softer and wetter than the syenite. The tunnel passes through all three types of material.

Around 1853 a shaft was begun and eventually 7 ft. pilot headings were driven from the bottom. The work progressed slowly and proved very expensive; a contemporary writer observed that "At the present time (February 1856) the tunnel is closed, and the works have been abandoned from want of funds to proceed with the railway; and it is very doubtful whether it can be carried on to Hereford for many years to come".

This could have been so had not Stephen Ballard entered the project in October, 1856. Ballard was a local man, born in Malvern Link in 1804 and possessed of that catholic talent which distinguished the engineers and scientists of his age. Thomas Brassey, the great railway constructor, had engaged him as agent and partner in several of his contracts and this became his position in the Worcester and Hereford Railway project. By that time he was living at Colwall, on a farmstead whose land lay over the tunnel route.

Things began to buck up. A new Act of August, 1858 enabled funds to be subscribed by the railway companies associated with the Worcester and Hereford Railway, as distinct from merely local interests. Anticipating this Ballard prepared a new design for the tunnel and in February, 1857 set miners to work extending the heading into the hillside. In those days all the rock cutting was by hammer and hand drill, sometimes assisted by blasting. In May, 1857 Ballard experimented with a steam drill, but it was not a success. On 21st February, 1859 he records that 9 men and 3 drills were working the headings, for which each was paid three shillings for a 10 hour day. The extraction rate was a mere 7 ft. 6 in. per week.

Obviously more working faces were needed for the tunnel to be completed in reasonable time; some 693 yards had to be cut through the syenite; so a second shaft was begun on Ballard land on 28th January, 1860, and later a third. A locomotive was hauled over the Hills by horses and put to work hauling spoil from the Colwall workings. The syenite was not the only problem. The bore intercepted water courses and drained the wells on the hillside, to the displeasure of both miners and residents. Pumps had to be installed and the water piped up to the houses. A stationary steam pump at the foot of an air shaft was a feature of the old tunnel during its working life.

The laborious extraction continued until a way through was made on 21st July, 1860. On 17th September, 1861, the tunnel work was completed and the Worcester and Hereford Railway opened throughout its length.

The growth of traffic was rapid, and by the middle of 1868 there were no less than 44 scheduled services a day passing over the single line through the tunnel. Most were freight trains to and from the Midlands and the coalfields of South Wales. Banking engines helped heavy westbound trains through the tunnel. The vibration from this traffic and the action of the smoke caused severe deterioration of the brickwork. Within a year there was a fall of rock from an airshaft. There was a similar fall in 1907 and later on there were stories of trains emerging with dislodged bricks stuck in the coach roofs. By the early 1920's the old tunnel was almost worn out.

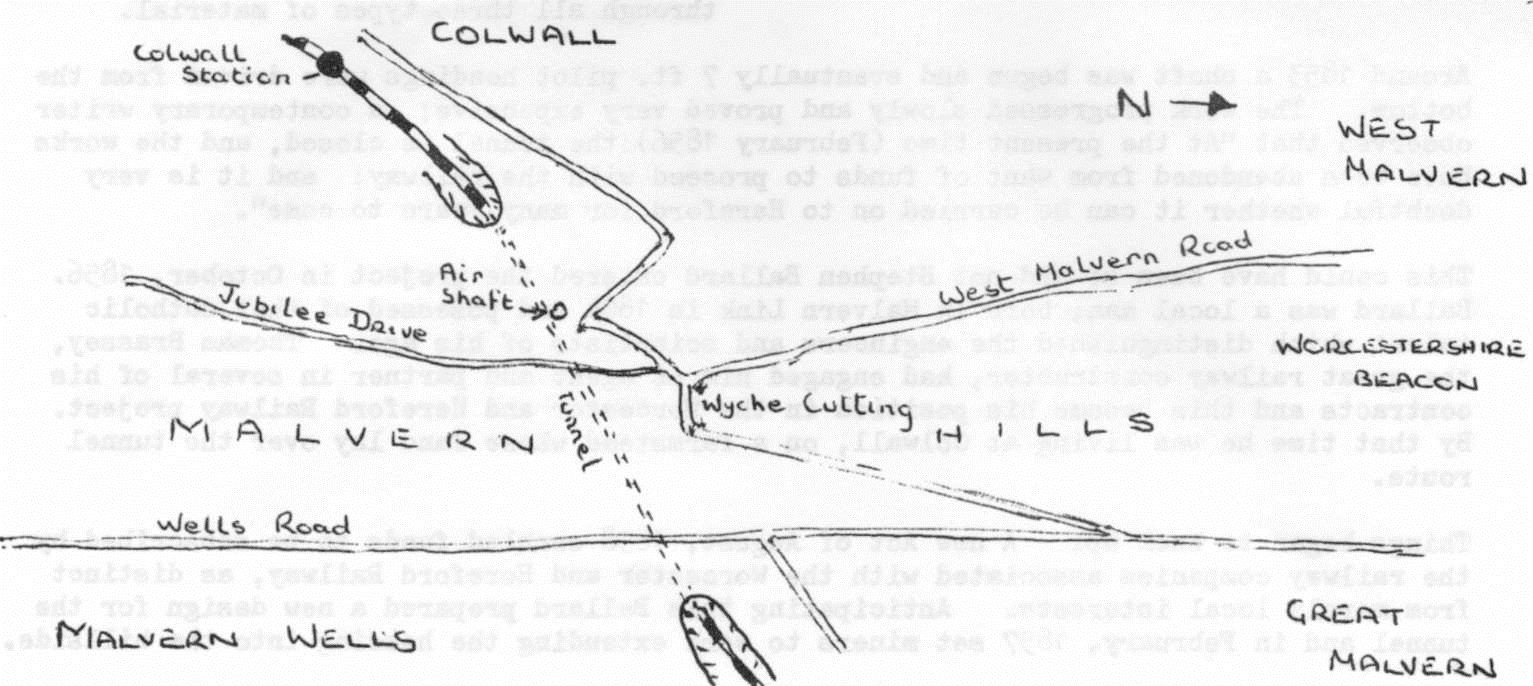

One of the old ventilating shafts can be seen near the first hairpin bend on the road from the Wyche Cutting to Colwall. Another in on Ballard land, and close by it is Stephen's grave. He died in 1890, his long life crowded with wide achievements in waterways and railways. He would have appreciated a later irony. As railways gave way to roadways the syenite spoil which had been dumped near the tunnel was taken away and used as ballast for the M50 motorway.

The New Tunnel

On the 18th July 1923 Royal assent was given through the GWR Act 1923 authorising the construction of a second Colwall tunnel and associated line realignments.

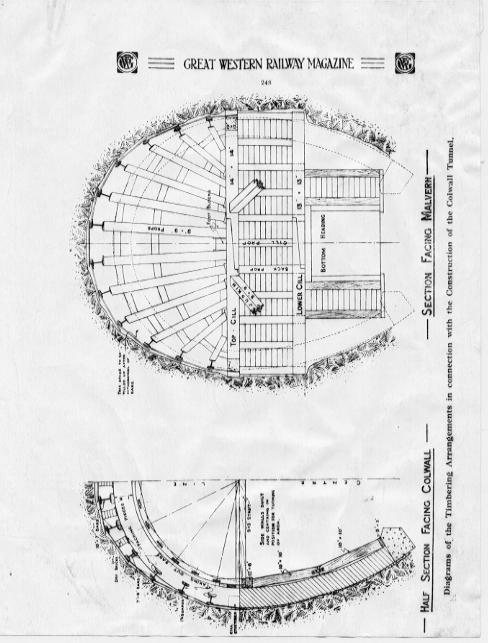

The new tunnel had a substantially larger bore and a different cross-section. The original tunnel had a semicircular arch with vertical side walls 16 feet high and was 12 feet wide. The new tunnel by contrast was horseshoe shaped, 18 feet high and 17 feet wide. It also had a less steep gradient (1:90). It was located close enough to the original tunnel so that it could utilise the original ventilation shafts by means of cross bores.

The work on the new tunnel commenced in 1924 from both the Colwall and Malvern Wells ends and by July 1925 the headings of the new tunnel met in the middle.

By 1926 Colwall station and goods yard had been remodelled as part of the new tunnel workings, and the Colwall signal box had been replaced by a cabin that was located at the Worcestershire end of the 'Down' platform. The spoil from the tunnel was piled by the side of the Malvern Wells entrance and later removed to form hardcore for motorways. On the 2nd August 1926 the second Colwall tunnel was opened and rail traffic was immediately transferred to the new tunnel. The cost of building the tunnel was £196,080.00 (equivalent to £14,164,677.00 in 2022).

Old Colwall Naval Armaments Store

Although the original tunnel was taken out of service as a railway tunnel when the new tunnel was opened this did not represent the end of its use. In the Autumn of 1939 repairs were made to the lining of the tunnel and a concrete floor was laid so that it could be used as an Admiralty armaments store. The official title of this store was Old Colwall Naval Armaments Store (OCNAS). The OCNAS came under the control of HMS Duke, a wartime naval training establishment in Malvern. (The site later became the Royal Radar Establishment (RRE) now QinetiQ.)

A company of soldiers, of up to forty men, was stationed at each end of the tunnel to guard it and check everyone entering and leaving. They were housed in concrete barracks at Colwall station on the embankment behind the 'Down' platform. Later the barracks were converted into bungalows. The guards were housed in smaller huts close to each end of the tunnel whilst on duty. The armaments were normally dispatched within two days of arrival and so the tunnel would have been operated more as a distribution centre than a store. As an aid to operating the OCNAS, a narrow gauge (18 inches) railway was laid within the tunnel, worked by two Ruston & Hornsby diesel locomotives.

Given that the use of the OCNAS during World War II was secret there is very little information available about what went on. However, fragments of an old ledger have survived and imply that many of the armaments came from the Royal Ordnance Factory at Rotherwas, Herefordshire, along with armaments from Bristol and Woolwich.

After the war, the narrow gauge railway was dismantled, and the two locomotives were sent to the Admiralty Depot at Bull Point, Devon. The tunnel mouths were then sealed with steel sheeting. The original tunnel is now home to a colony of lesser horseshoe bats. There have been moves to get the original tunnel reopened for recreational use and the Colwall Tunnel Project assessed the potential to open it as a cycling and walking route. To date this has not come to fruition and so currently the bats still hold the roost.